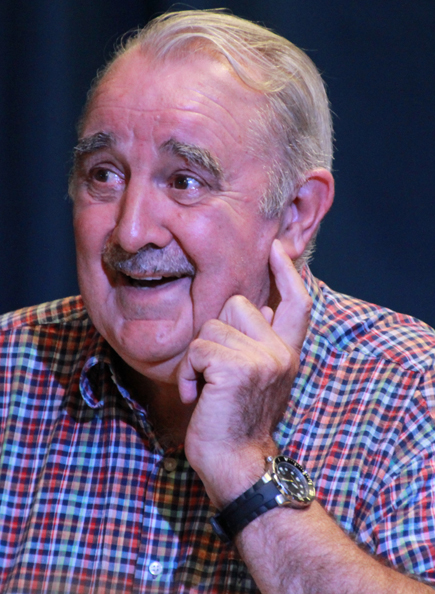

The voices of the Parcnest Boys must have been specifically made to recite the poetry of their literary hero, Waldo Williams. The mellifluous tone of the Dyfed dialect could be heard in the voice of the youngest of the three, Aled Gwyn, as he quoted extensively from the poet’s poems when he delivered the Annual Cymdeithas Waldo Lecture, based on a line from the ‘In Two Fields’ poem – ‘Mor agos at ei gilydd y deuem’ – which translates as ‘how close to each other we became’, at Puncheston in North Pembrokeshire on Friday September 26 2014. Questions had been raised beforehand regarding a possible grammatical error in the quoted line. This had been mentioned by author Alan Llwyd who launched his own biography of Waldo Williams the same evening. His assumption was based on a copy of the original poem in Waldo’s handwriting published in his book. Indeed there was a slight difference in spelling. How would the guest lecturer respond therefore? Well, with nonchalance. His interpretation was taken from the accepted published version in the volume Dail Pren.

Aled Gwyn posed the question why had the ‘error’ not been corrected in the subsequent published versions? Why had it not been spotted by the original proof readers? Why had Waldo himself never drawn attention to the matter? He maintained that Waldo possibly saw the error as an improvement on the original as it reflected the peculiarity of the Dyfed dialect. However, the lecturer declared that such a grammatical spat did not impede the meaning of the words which convey the tremendous empathy Waldo had towards his fellow human beings.

As an ordained minister of religion Aled Gwyn referred to Paul’s advice to Philemon and Onesimus, despite being master and slave, to be kindred brothers in Christ. He also referred to a recent statement by a Catholic bishop who felt he was one with Pope Francis. In other words he did not feel that the current Pope was in any way above him. That was Waldo’s defining message, to be able to be as one with one another. The lecturer further explained the phenomenon by referring to what he called the ‘neurone empathy’ within the animal kingdom. The healthy monkey will instinctively aid his sick compatriot.

Aled Gwyn saw this incredible talent at first hand when he visited Waldo at St Thomas’ Hospital in Haverfordwest. Despite his own misfortune he wanted to know what had happened to his fellow patient in the next bed who had been taken to Glangwili Hospital at Carmarthen. He wanted to know what was the fate of those members of the younger generation who quoted his poems in court proceedings as they fought for the future of the Welsh language. Their indulgence in acknowledging his poems in such a manner gave him a warm glow. After all, he had given his volume of poems, Dail Pren, as a means of healing his nation. Aled asked himself from where had Waldo received this precious ability which he described ‘as the ability to understand other people’s suffering which in turn continues to inspire us today’. He maintained it all emanated from the hearth. He imagined Waldo listening to his parents as they read the poems of Tennyson and others under the oak tree where they spent so much of their time at Parc y Blawd – the Flour Field – in Llandysilio. As a result that quiet strength of mind along with the sweeping power so characteristic of his personality and embodied in such poems as ‘Preseli’ and Tyddewi’ were nurtured.

A lecture on Waldo would not be complete without reference to his idiosyncrasies and humour. We were told about his behaviour on the day of the anti-Investiture rally at Caernarfon in 1969. He had left home early that morning and had walked some distance. Aled saw him at the Owain Glyndwr Parliament café in Machynlleth. He complained bitterly about his feet -‘my corns are almost killing me’. He was hardly in a mood to discuss the political implications of the investiture. When the rally parade was about to start he disappeared because he suddenly declared, ‘I must have a piece of meat for tomorrow’s dinner’! When he stood as a parliamentary candidate in Pembrokeshire in 1959 he was given a warm welcome in the village of Trefin. In fact he visited the village on three occasions such was the hospitality given to him and his fellow canvassers. However, when it came to the actual count few votes for Plaid Cymru were seen in the Trefin box compared to the Labour and Tory votes. Waldo did not denounce the villagers nor share the disappointment of his agent Eirwyn Charles, a native of the locality, but rather composed a hasty poem showing him to be the epitome of everlasting hope. Despite their sterling work at the time he foresaw that the fruits of their efforts would be seen at another time in the future.

Aled Gwyn drew attention to the irony of remembering a resolute pacifist that evening when earlier in the day the Westminster parliament had decided to join in the bombing of Islamic insurgents in Iraq. He insisted that Waldo’s brotherly empathy would be with ‘the cold and dead villages full of human skulls’. He referred to the former armaments depot at Trecwn where workers once spent a week packing bombs to be sent to India and the following week packed bombs to be sent to Pakistan in order to maintain the war between the two countries.

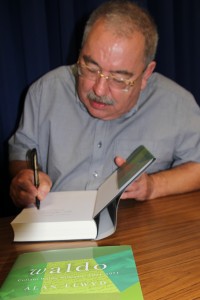

As he launched his biography Alan Llwyd thanked David Williams – one of several of Waldo’s nephews present – for showing him previously unseen material which threw fresh light on many of his uncle’s poems and indeed for finding poems that had not been previously published. And in his comments earlier in the evening as he unveiled a memorial stone on the verge of Puncheston Moor, Emyr Llewelyn, who also knew Waldo well, emphasized his stature as a poet of eternal hope. He referred to the poem ‘Ar Weun Cas’mael’ (On Puncheston Moor) where the bard refers to the gorse in bloom once again and the lark bursting into song high above as symbols of an eventual end to all wars. The poem ‘Y Tangnefeddwyr’ (The Peacemakers) was sung by Côr Abergwaun (Fishguard Choir) at the outset of the evening. The evening’s events were linked by Cerwyn Davies, chairman of Cymdeithas Waldo, in his usual homely manner. At the end refreshments were served to enable all those present to socialize and buy signed copies of Alan Llwyd’s book.